Having been mostly raised in a remote Northern New Mexican town, red and green chile were to me what matzoh is to the Mossad or potatoes are to the little carrot-topped rascals frolicking through the clover-laden hills of Eryn. If New Mexicans did not already bleed red, we would bleed green and we would bleed proudly.

Green and red chile are fixtures in New Mexican cuisine. Just as diabetics need insulin and hypochondriacs need pity, New Mexicans need chile in a way that most behavioral psychologists would classify addiction.

Physiologically, capsaicin - the oily compound found in peppers that creates the sensation of warmth on one's tongue and inner cheeks - creates an identical neural response to being burned. Scientists describe it as such:

"Capsaicin, as a member of the vanilloid family, binds to a receptor called the vanilloid receptor subtype 1 (VR1). VR1 is an ion channel-type receptor and can also be stimulated with heat and physical abrasion, permits positively-charged ions (i.e. cations) to pass through the cell membrane and into the cell from outside when activated. The resulting 'depolarization' of the neuron stimulates it to signal the brain. By binding to the VR1 receptor, the capsaicin molecule produces the same effect that excessive heat or abrasive damage would cause, explaining why the spiciness of capsaicin is described as a burning sensation."

Translation: the feeling one experiences when biting into a jalapeno, the feeling that is perceived and referred to as "hot," is in fact the simulated effect of fire without having the realization of any of the consequences of fire. Capsaicin is amazing in its ability to trick our neurons into believing that scorching heat is actually being applied to our tongue, even though all that's really being applied is a waxy, oily necklace of carbons. "Why is this amazing?" you ask. Well, I'll tell you.

Capsaicin is amazing as a compound because I can think of no other food that has the power to simulate a neural response in the actual absence of the initiating mechanism. Have you ever eaten cheese and feared that your tongue was going to get frostbitten? Or have you taken a spoonful of yogurt and felt that your tongue were being cut open by razor blades? Did the milk that you had at breakfast, the milk that you know to be silky and smooth to the touch, feel coarse when you slurped it up? Your response to all of these questions, of course, is no.

In general, foods do not invoke the sensation of being harmed, and if they do we tend to avoid them. Thistles and burrs may be nutritious indeed, but the act of eating them tends to be unpleasant, so we generally avoid putting them in our mouths (unless stranded in the woods with no nourishing alternatives). But this is not the case with chiles.

In this sense mentioned above, the sensation of eating chile is almost synthetic because it creates a response that is not actual in the objective sense of the word; we are not being burned, it only feels, subjectively so, that we are being scorched. We feel as though we're being burned when we eat chiles, but in reality, we are not being burned at all: our tongue does not blister, we do not apply medicinal balms to the inside of our mouth, and neither does a scar form where the chile touched our skin. And it is the fact that we are not being burned, this encapsulated and secure sense of safety, that causes many people to love chile so; like rollercoasters, we get the intense sensation - the "rush" - without the threat of the dangers.

However, it should be noted that, as we have not all mastered the art of mind over matter, certain doses of capsaicin can fool our body into having adverse responses. Even though we know eating a jalapeno, while oftentimes unpleasant, will not really singe us or cause bodily harm, if the chile is hot enough our body will react with startling alarm. We will begin to sweat profusely. Our eyes will water. Our brow will stipple with sweat. Our nose will run. Maybe we will get the hiccups. Maybe the pain will become so unbearable that we experience a loss of hearing, sense of direction, sense of self, ability to speak, or suffer the impairment of other faculties we take for granted.

Today at the 18th Annual Fiery Foods Festival I met my match. Even though I'm a transplant to the Southern Rockies, I consider myself a New Mexican: I like my chocolate better with a little chile in it, I've sampled green chile beer, I can find applications for chile for all three meals of the day and on every strata of the food pyramid, and I frequently complain of food that reddens others' faces as being "just not hot enough." Black pepper is bland to me, that's how New Mexican I am.

In general, I was disappointed with the Scoville Heat Unit (the scientific measurement of the quantity of capsaicin per volume) of 90% of the products I sampled at the FFF: peach salsa, mango salsa, wasabi green tea dipping sauce, smoky BBQ rubs, cabernet sauvignon jelly, chocolate and red chile coated pecans - they all tasted great, but none of them made me feel like I'd committed an unforgivable sin and was being given an afterlife sneak-preview. Even the Screaming Monkey Hot Sauce, which burned like a brand at first, eventually wavered. Another hot sauce, Defcon, didn't live up to the macabre sound of the title it was bestowed.

My friend Marky - who accompanied me to the FFF - and I ran into a trio of acquaintances, all three of whom were fanning their mouths after trying something called Montezuma's Revenge. I quickly jumped at the chance to sample what it was that was making these Native New Mexicans pant like Iditarod sled dogs. After sampling Montezuma's Revenge Marky found it to be unbearable and she quickly left my side to buy the $6 margarita she had only minutes earlier balked at. I tolerated the pain, not finding it unpleasant enough to shell out money for an overpriced mixed drink.

Another sauce, which was called XXXXXX, put Screaming Monkey to shame, but it still didn't put me over the edge. My friend Adrian, as evidenced through his perspiring, had a different opinion of XXXXXX. When he took a dose of XXXXXX, which he boasted he'd tried before and found not to be terribly unpleasant, a strange thing happened: within seconds he looked as though he'd been thrown into cauldron. He grimaced, his eyes began to tear, his face turned a deep red, and his tongue, too busy battling the bonfire XXXXXX had induced, could no longer form coherent syllables, let alone string them together as a sentence.

Continuing on my quest to find the hottest substance known to man, I was directed to a man at a nearby booth who used a pair of tongs to handle his chips and salsa. This intrigued me, as it gave the salsa a certain sense of dire toxicity. I asked the salseur for the hottest thing he had. He blasted some on a chip and handed it to me. I made sure to chew the chip for a good twenty seconds so the hot sauce could spread evenly across my tongue. Then I swallowed. Waited. And again was disappointed. Though it was the hottest thing I'd tried all day, though my tongue felt as though an Indy car had peeled out on it, I was unsatisfied. My eyes weren't watering, my face wasn't red, I didn't have the hiccups, and neither was I seeing stars.

The trio of panting acquaintances from earlier passed by again, this time bragging that they'd found the hottest fare in all the fair. With my tongue still burning from the ghost of XXXXXX and the tong thrashing, I followed them dutifully to a kiosk and was told to ask for "the Boost." I have to admit, The Boost was an intimidating ration: one whole tortilla chip is lathered in hot sauce and then the wetted chip is doused liberally in a chile powder rub. Simply for trying The Boost you're awarded a sticker in order to boast your feat. However, whether or not samplers of the notorious nosh survive to tell their friends about their XXXXXX-ploits was something I had yet to determine.

I again chewed the chip thoroughly and then swallowed. The Boost was hot, but I refused water and alcohol from friends who were obviously expecting me to lose my cool at any minute. It wasn't so much the pain in my mouth that bothered me after trying as the sense of dizziness and horrific stomach ache that followed. After some ice cream, lots of lemon-faced expressions, and twenty minutes in an air conditioned car, I finally felt normal again.

But I had done it. I'd taken a big bite right out of hell and though I won't put on airs and say I was unphased by XXXXXX, The Boost, or the litany of other conflagrating condiments I sampled, I will say that maybe capsaicin can lick my tongue, but I can kick its ass.

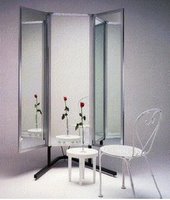

A few blocks later he walks into a haberdashery and goes immediately to a trio of full length mirrors. The tailor smiles at him and then, seeing the look of worry in Montgomery's eyes, drops his smile. Montgomery turns his head to look at the wound reflection off the juxtaposed mirrors and he sees blood running down his neck and staining his suit. But he also sees much dried blood on his suit, faded and much older than the blood gushing from his new wound. He sees that he has been bleeding down the back of his neck and staining his suits for years. He sees that, from the time he was a child, he has never stopped bleeding.

A few blocks later he walks into a haberdashery and goes immediately to a trio of full length mirrors. The tailor smiles at him and then, seeing the look of worry in Montgomery's eyes, drops his smile. Montgomery turns his head to look at the wound reflection off the juxtaposed mirrors and he sees blood running down his neck and staining his suit. But he also sees much dried blood on his suit, faded and much older than the blood gushing from his new wound. He sees that he has been bleeding down the back of his neck and staining his suits for years. He sees that, from the time he was a child, he has never stopped bleeding.